Introduction

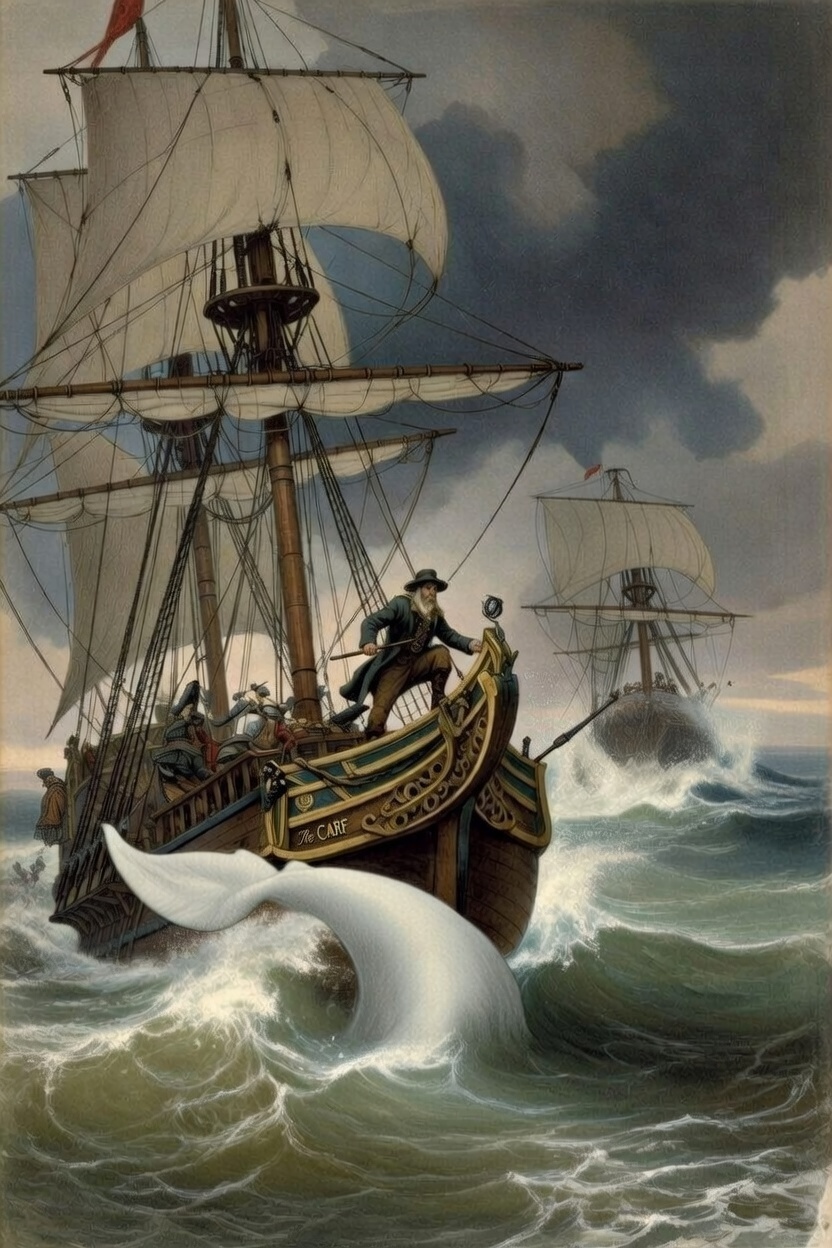

“Call me Ishmael” famously begins Moby Dick. And now, as it happens, so does this article.

But whereas Melville’s book is about Captain Ahab’s unhealthy obsession with a white whale, this article is about a different kind of whale. Crypto whales: individuals and groups whose crypto holdings are large enough to matter.

Ahab’s harpoon was made of iron. In our crypto whale hunt, the harpoon is information. And from 1 January 2026, for HMRC and other tax authorities around the world, the sharp end of that harpoon will be the Crypto-Asset Reporting Framework… or CARF.

[It should be noted that CARF does not only apply to ‘whales’. It will apply to the wider crew too: ordinary retail investors and small traders. But that would ruin my Moby‑Dick theme. And, like Ahab, I can’t quite give it up].

CARF in plain English

So, what is CARF?

CARF is the OECD’s attempt to do for crypto what earlier transparency standards, namely the Common Reporting Standard (CRS), did for offshore financial accounts. In other words, it aims to standardise the information around crypto transactions that gets collected, who collects it, and how it is shared between tax authorities.

The OECD has been fairly blunt about its motivation. Crypto grew quickly, and policy-makers did not want the gains made more generally in global tax transparency to be gradually eroded by certain assets moving outside existing reporting systems.

Unsurprisingly, the UK policy objective reads the same way. It is designed to support CRS and to give tax authorities a structured, annual stream of tax-relevant crypto information.

What has changed in the UK?

From 1 January 2026, the UK’s implementation of the CARF regime moved from consultation and guidance into live legal obligations through the Reporting Cryptoasset Service Providers (Due Diligence and Reporting Requirements) Regulations 2025 (SI 2025/744).

That is a mouthful, even for a whale. So, for the purposes of this article, I will call them the UK CARF Regulations.

Crucially, these Regulations are the UK’s domestic implementation of the OECD CARF framework. They take CARF’s due diligence and reporting rules and make them enforceable in UK law, with reporting directed to HMRC.

The practical starting point is simple

If you provide cryptoasset services in the UK and fall within the definition of a Reporting Crypto-Asset Service Provider (RCASP), you must collect data and report it to HMRC.

In broad terms:

- You must collect details of all users.

- You report users who are tax resident in the UK and users tax resident in other CARF-participating jurisdictions.

- The first reporting period is 1 January 2026 to 31 December 2026.

- The first UK report is due between 1 January 2027 and 31 May 2027 (and annually thereafter by 31 May).

For the first time, many crypto platforms will be required to produce a standardised annual “shadow statement” of customer activity. For the avoidance of doubt, this is not for the customer, but for the tax authority.

This is perhaps enough to send shivers through the timbers of any crypto degen.

Who has to report?

CARF is designed around reporting by Reporting Cryptoasset Service Providers (“RCASPs”). These are entities that, as a business, effectuate exchange transactions on behalf of customers.

The definition is intentionally broad, because any compliance regime can be made toothless if its perimeter is drawn around yesterday’s business models.

In practice, RCASPs will include:

- Centralised crypto exchanges (crypto-to-fiat and crypto-to-crypto trading – think Coinbase and Binance to name but two).

- Brokers and dealers executing trades for clients.

- OTC desks arranging and executing large exchange transactions.

- Operators facilitating cash-to-crypto conversion (for example, crypto ATMs) where they are effectively providing an exchange service.

Depending on the facts, certain non-custodial services may also be caught if they are considered to effectuate exchange transactions, rather than merely providing software.

A few short voyages into the make belief illustrate when reports arise:

Example 1: Alan:

Imagine Alan opens an account with a UK‑based exchange. Let’s call it “ThamesX”. He self‑certifies that he is UK tax resident (providing the usual identifying details the platform needs for due diligence).

During the 2026 reporting year he makes a handful of transactions:

- 15 January 2026: buys 0.50 BTC using £15,000.

- 20 March 2026: swaps 0.20 BTC for 6.0 ETH (a crypto‑to‑crypto exchange).

- 2 July 2026: withdraws 3.0 ETH to his own external wallet (a transfer off‑platform).

- 18 November 2026: sells 2.0 ETH back into GBP and withdraws the cash to his UK bank account.

In broad terms, the CARF report to HMRC would link Alan’s identity and tax residence to the activity the platform facilitated.

It is not a tax computation, but it will typically include:

- identifying details and tax residence information,

- the platform account identifier, and

- details of reportable transactions such as the type of transaction (fiat‑to‑crypto, crypto‑to‑crypto, crypto‑to‑fiat and relevant transfers), the cryptoassets involved, the units, the date/time, and the value used for reporting (plus any fees).

That is enough for HMRC to “story test” the return, If, say, Alan reports nothing, the information reported under CARF tells a different yarn.

Example 2: Betty

Now imagine Betty. She is not UK tax resident. She lives in Paris and self‑certifies that she is tax resident in France (a CARF‑participating jurisdiction for the purposes of this example). She nevertheless uses the same UK exchange (“ThamesX”) because it offers the trading pairs she wants.

Over the year, Betty buys £8,000 worth of USDC, swaps it into SOL, and later sells back into GBP to withdraw funds to her UK account while she is on assignment.

The UK exchange still has to do due diligence and still has to compile a CARF report because it has facilitated exchange transactions for a reportable person.

The mechanics can feel counter‑intuitive: the UK platform reports to HMRC first, and (once exchange relationships are live) HMRC can exchange the relevant report with Betty’s home tax authority.

In practice, the information shared with the overseas jurisdiction would be the same core dataset as in Example 1.

Example 3: Charles

Charles is UK tax resident but chooses to trade on an overseas exchange. That platform based in another CARF‑implementing jurisdiction (for example, an EU‑based exchange). He self‑certifies his UK tax residence when he signs up, and the overseas exchange facilitates a series of trades and withdrawals during 2026.

For instance, Charles buys £12,000 of ETH, swaps some into SOL, and later sells back into euros before withdrawing to his bank account. Under CARF, the reporting route is reversed compared to Alan. The overseas exchange reports to its home tax authority, and HMRC can receive the information from that authority through automatic exchange.

Charles may feel he is trading “offshore”, but CARF is designed as a fleet: if the jurisdiction participates, the logbook can still wash up on HMRC’s desk.

Example 4: OTC – Davina & Edgar

Over the Counter (“OTC”) desks are where whales often surface. Imagine Davina and Edgar each have verified accounts with a UK OTC desk called “Mayfair OTC Ltd”. Davina wants to sell 25 BTC; Edgar wants to buy 25 BTC without moving the market on a public order book.

The desk agrees the price, provides settlement instructions, and executes the exchange. For example: Edgar sends £1,000,000 to the desk’s client money account; Davina sends 25 BTC to the desk’s designated settlement wallet. Once both legs are confirmed, the desk releases the BTC to Edgar and the GBP to Davina (minus its fee).

From a CARF perspective, the OTC desk has effectuated an exchange transaction on behalf of customers, and so it can sit squarely within the RCASP perimeter. The report to HMRC would typically record each customer’s identity/tax residence and the details of the exchange transaction it facilitated (asset, units, timing, value, fees).

Example 5 – Crypto ATM – Edgar

Finally, consider Francesca, who operates crypto ATMs in the UK.

A crypto ATM is, in effect, a kiosk that lets a customer exchange cash (or sometimes card payments) for crypto, or crypto for cash, typically by routing the transaction through the operator’s liquidity provider and wallets.

Edgar walks up to one of Francesca’s ATMs and buys £300 of BTC. He enters a wallet address (his own hardware wallet address, for example) and the machine sends BTC to that address once the payment is taken.

Alternatively, in a sell‑to‑cash flow, Edgar might send BTC to an address displayed by the ATM and, once confirmed, collect cash from the machine.

Where the operator is effectively providing an exchange service as a business, CARF is designed to treat that as reportable activity.

The operator’s records (and therefore the CARF report) would focus on who the customer is and what exchange transaction was facilitated: when it happened, what asset was bought/sold, the units, and the value used for reporting (plus fees).

What is the position when it comes to self-custody?

Consider Godfrey, a UK taxpayer who holds Bitcoin in self-custody on a hardware wallet – for example, via a Nano Ledger or similar. So, we are talking ‘your key, your crypto’ folk here.

Of itself, merely holding BTC off-exchange does not automatically result in an obligation for anyone to produce a CARF report.

But Ben’s activity is not invisible.

For example, it is likely at some point that he needs to use an ‘on-ramp’ and / or ‘off-ramp’.

For example, If Ben buys BTC on an exchange using GBP, that purchase is visible to the exchange and is likely reportable under CARF.

On the other side of the crypto coin, if he withdraws the BTC to his own wallet, the exchange will also have a record of a reportable withdrawal.

Similarly, if Ben later deposits BTC back to the exchange and sells it for GBP, the off-ramp trade is again visible and potentially reportable.

The point, therefore, is not whether CARF “covers” self-custody. It does not. The point is that CARF captures the choke points where crypto meets the regulated perimeter. It is these choke points that will leave a trail.

What CARF is not

There is one large mammal in the room (a four legged one with a long nose, rather than a marine dwelling one). Many people assume CARF is a new “crypto tax”.

It is not.

In the UK, the underlying tax rules have been in place for some time. Most straightforward disposals and exchanges can be analysed under existing principles. There are, of course, areas where things get more complex (DeFi, wrapped assets, staking rewards, and questions such as situs), but CARF is absolutely not attempting to rewrite the tax code.

CARF is about information sharing, not tax liabilities. It changes what HMRC can see, how quickly it can see it, and how easily it can compare third-party information against what a taxpayer declared (or did not declare).

Why HMRC cares

HMRC already has information powers, and it already uses them.

But automatic third-party data is a force multiplier. When information arrives structured, consistently, and at scale, it enables:

- Faster risk scoring and triage.

- Targeted nudge campaigns (letters, prompts, compliance checks).

- More efficient enquiry selection.

- Quicker “story testing” (does the return make sense against the activity stream?).

In other words, CARF is better understood as a compliance engine than as a technical tax reform. It is perhaps the difference between randomly firing a harpoon into the water and using a laser-guided one.

Data iceberg ahead

CARF is sometimes discussed as if it is a simple pipeline. Platforms will report your activity, the tax authority matches it, job done.

But reporting regimes do not usually fail because the legislation is badly drafted. They fail because the data is messy.

The crypto industry has a credibility problem here. Many users already struggle to obtain clean, complete and consistent statements of activity from every platform they have used. Yet CARF assumes those same systems can now produce accurate annual reports at scale.

Even where everyone acts in good faith, there are obvious fault lines:

- Missing transactions and partial histories (migration between systems, delisted assets, historic outages).

- Duplicated or double-counted records if multiple actors are treated as having “effectuated” the same exchange transaction.

- Inconsistent categorisation (what is a trade, a transfer, a reward, an airdrop, a staking return?).

- Inconsistent valuations and timestamping across platforms.

- Identity mismatches (changes of name, address, tax residence, entity classification).

Add in the reality that many taxpayers have activity spread across multiple exchanges, multiple wallets, and multiple chains, and you have the ingredients for disputes.

HMRC’s penalty framework adds pressure. Providers can face penalties where reports are inaccurate, incomplete or unverified, and users can be penalised for failing to provide required self-certifications. That may be necessary to make the system work. But it also raises a practical question: when the reporting data is wrong, who bears the pain of proving it?

For the rule-abiding taxpayer, the concern is not that CARF creates a new tax charge. The concern is that CARF can create false confidence in flawed data. If the machine says one thing and reality says another, a human being, often a compliant one, will be the person doing the work to reconcile it.

Corrections, disputes and false positives

The designers of CARF know errors are inevitable. The OECD’s technical materials explicitly contemplate corrections and status messages. That is sensible. But it is also an implicit admission that the system will generate fixes, amendments and disputes.

Large-scale analytics also creates false positives. Anyone who has worked a tax enquiry might have seen the pattern before. A data mismatch triggers a question, the question triggers an information request, the information request triggers a long exchange of explanations and evidence.

The darker by-product

If you are squeamish, you may want to look away.

Operated properly, the dataset collected under CARF will be immensely valuable to HMRC and other revenue authorities. It will identify patterns, connect identities to activity, and help close gaps. It should also do this much more quickly than under present powers.

But the same dataset is also attractive to criminals. In most tax contexts, the harm of a leak is primarily financial. For example, fraud and identity theft.

However, Crypto data in the wrong hands has already shown a different risk – A very physical and very violent one.

Last month, French newspapers described violent attacks linked to crypto holdings, including a home invasion in Verneuil-sur-Seine where a family were bound and beaten. More chilling was an adjacent allegation: that a tax office employee had exploited access to internal tax software to search for targets, including cryptocurrency investors.

The instinctive UK reaction might be that it “couldn’t happen here”. However, again, just last month, there were reports of two HMRC officers charged with passing confidential taxpayer information in exchange for payment. Whatever the outcome of that case, it is a reminder that insider risk is not a foreign curiosity.

Nor is it only a public-sector problem. In 2025, Coinbase publicly described criminals bribing and recruiting overseas support agents to steal customer data to facilitate social engineering.

Crypto also has its own inherent fragility. Traditional financial accounts impose more friction. A bank will usually have payment rails, reversals, and account flags. With crypto, and particularly with self-custody, the control layer may simply be a person holding a USB-sized device.

Physical coercion has become a recurring theme in reporting about crypto-linked kidnapping and extortion. In January 2025, David Balland, a co-founder of French crypto firm Ledger, was kidnapped and had his hand mutilated.

None of this is evidence that CARF will lead to widespread violence. But if CARF helps compile and move richer datasets about who has meaningful crypto wealth, it should also force an adult conversation about security, access controls, auditing, and what happens when the list escapes.

Conclusion

CARF will cause friction. It will generate noise. It will produce disputes. And it may feel like a car crash for a while, especially where exchange records are incomplete and formats do not line up.

Of course, none of this is a serious argument for carving crypto out of the tax system. It is a call to arms on two fronts:

- For institutions: Treat CARF data as critical infrastructure. Errors and failures will likely lead to penalties. Additionally, the data should be protected internally as insider risk is not hypothetical.

- For taxpayers (especially whales): Firstly, they need to be aware that transparency has been cranked up a level or two. Secondly, they also need to treat operational security as part of financial planning, not as paranoia, because in crypto the consequences of being “on a list” in the wrong hands can become personal.

Ahab did not meet his end because he hunted the whale. He lost because his obsession made him blind to the risks around him.

Many in the industry might be hoping that CARF is a white elephant rather than a white whale. But I would urge both RCASPs and crypto investors to make sure they are familiar with the information sharing obligations posed by CARF.

Because tax authorities, including HMRC, wait with their shiny new harpoon.

If you have any queries about this article, then please let me know.